How is history written and by whom? These are questions that have been raised with frequency across the decolonising movement and in particular, by the Cadaan Studies movement, which has focused on knowledge production relating to Somali people. Started in 2015 by Harvard doctoral candidate, Safia Aidid, the movement provides a framework through which to critique the role of whiteness and white privilege in shaping narratives about Somali people. The canonical work of Glaswegian-born I.M. Lewis has come under particular scrutiny not in the least due to his twin roles as anthropologist and administrator for the British colonialists in (then) British Somaliland in the 1950s. Yet whilst the colonialist activities of a Scotsman in Somalia shaped global discourses about Somali people, the narratives of Somali people in contemporary Scotland, many of whom now live in the same area of Glasgow in which Lewis was born, remain absent from local and transnational histories. We unravel and critique this absence.

Today in Scotland, there is a Somali population of up to 4000 people. The population has grown in the main since 1999, following the state-enforced dispersal of asylum seekers to sites around the UK. Despite residing in Scotland for nearly two decades, the Somali population continues to be framed in these terms, considered ‘new’, as ‘migrant’; as without history prior to arrival in Scotland and without historical links to Scotland.

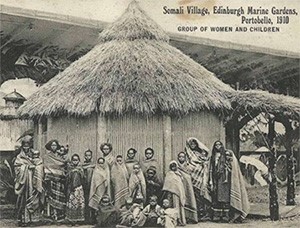

Members of the ‘Somali Village’ at Portobello (Freeman, 2015, p. 28)

These narratives obscure a much longer history of Somali people living in Scotland, and of Scotland’s relationship with Somalia.

Scotland’s role in the British Empire (Liinpää 2018) establishes a firm connection between the colonial activities of the UK and Somalia. The earliest evidence we could find of Somali people living in Scotland is situated firmly in this context.

Edinburgh’s ‘Somali Village’ was established in 1910 in its Marine Gardens, Portobello. A late example of what Sadiah Qureshi has termed a ‘human exhibition’ (2011), the village imported Somali families to live in a mud-hut compound and ‘perform’ their daily lives for visitors. Exhibitions such as the one in the Marine Gardens had a dual function: to place imperial ‘prowess’ on display and to reinforce white supremacy over the people on display. Edinburgh’s Somali Village remained popular until its closure just prior to the First World War, when its grounds were co-opted for war purposes. No record of what happened to the families remains.

On the other side of the First World War, the 1932 correspondence of Ali Mohamed, a Somali ex-seaman living in Glasgow, is the next trace of Somali settlement in Scotland. Facing destitution, and knowing of support for those who had served in the British Navy, Mohamed penned a petition to the (then) Colonial Office asking for assistance. His case caused some confusion in the Colonial Office – unclear about his status as a British ‘Protected’ Person (British Somaliland was a Protectorate not a colony) and noting that Mohamed resided in Scotland, the Colonial Office questioned Mohamed’s claim to citizenship and passed onto the (then) UK Government’s Scotland Office. The paper trail ends and we have not found evidence of what next happened to Mohamed. His letters come 7 years after the UK Government passed its Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seaman’s) Order, which restricted ethnic minority seamen’s access to the labour market. Laura Tabili describes the Order as ‘the first instance of state-sanctioned race discrimination inside Britain to come to widespread notice’ (1994, p. 56).

The final pre-1999 instance of Somali people living in Scotland is the case of Axmeed Abuukar Sheekh, a refugee who had been accommodated on the notorious Earl William prison ship until the hurricane of 1987. Following his release, Sheekh moved to Edinburgh with his family. In 1989, he was murdered after two white men took exception to his talking to a white woman. Ensuing police investigations have been described as mired in institutional racism, and to-date, no-one has been convicted of his murder. The handling of Ahmed Sheekh’s case has strong parallels with the investigation into Stephen Lawrence’s murder; however, Scotland has yet to have an equivalent national conversation about the impact of institutional racism on the people living within its borders.

The few traces of Somali people living in Scotland in the twentieth century trace a history of structural and institutional racism in Scotland. The accounts above make visible the ways in which the production of knowledge, control of territorial, economic and public space, and access to citizenship and justice were embedded in racialised and racist logics.

These cases and the contexts in which they occur are, of course, historically specific.

However, there is a case to be made that each instance in which Somali people are controlled, contained, excluded or erased the spaces they would otherwise occupy makes it easier for the next to do the same. Institutions, Sara Ahmed (2007) reminds us, are creatures of habit, which, through repeated action over time, normalise who ‘fits’ and who does not.

The brief histories of Somali people living in Scotland indicate that throughout the twentieth century, their containment by, exclusion from and erasure from public spaces in Scotland became institutionally habitual. Contemporary Somali-Scots populations have endured the UK’s asylum system, ethnic and racial penalties relating to employment, education and housing (Sosenko et al 2013), and ‘everyday’ and structural racisms. These experiences suggest that this a habit that is yet to be broken.

Yet within this context, resilient Somali communities are beginning to emerge. The last two decades have seen considerable population growth (from 159 Somali people in 2003 to the upper estimate of 4000 people today (Hill 2017)), as well as the development of businesses, and social and faith groups. There is scope within the Scottish Government’s progressive, pluralist rhetoric (Meer 2015) for meaningful and engaged conversations about what it means to ‘be Somali’ in Scotland today. However, with past precedents in mind, and noting the Cadaan Studies movement’s warnings about ‘voice’ and power, Somali-Scots must have space to speak for themselves for rhetoric to become reality.

Mohamed Omar FRSA works at the Mental Health Foundation within the Refugee Programme. Dr Emma Hill is a Research Fellow in Sociology at the University of Edinburgh.

References

Ahmed, S. (2007) ‘A phenomenology of whiteness’, Feminist Theory, 8(2), pp. 149-168.

Aidid, S. (2015a) After Cadaan Studies. The New Inquiry: The New Inquiry. Available at: thenewinquiry.com/essays/after-cadaanstudies/ (Accessed: 09/12/2016 2016).

Aidid, S. (2015b) Can the Somali Speak? #CadaanStudies. Africa is a Country: Africa is a Country. Available at: africasacountry.com/2015/03/can-the-somali-speak-cadaanstudies/.

Freeman, S. (2015) Beside the Sea: Britain’s Lost Seaside Heritage. London: Aurum Press.

Hill, E. (2017) Somali Voices in Glasgow City: Who Speaks? Who Listens? An Ethnography. PhD, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh.

Liinpäa, M. (2018) ‘Nationalism and Scotland’s Imperial Past’, in Davidson, N., Liinpäa, M., McBride, M. & Virdee, S. (eds.) No Problem Here: Understanding Racism in Scotland. Edinburgh: Luath Press, pp. 14-31.

Meer, N. (2015) ‘Looking up in Scotland? Multinationalism, multiculturalism and political elites’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(9), pp. 1477-1496.

Qureshi, S. (2011) Peoples on parade: exhibitions, empire, and anthropology in nineteenth-century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sosenko, F., Netto, G., Emejulu, A. and Bassel, L. (2013) In it together? Perceptions on ethnicity, recession and austerity in three Glasgow communities. Edinburgh: CRER.

Tabili, L. (1994) ‘The construction of racial difference in twentieth-century Britain: the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order, 1925’, Journal of British Studies, 33(1), pp. 54-98.